History of the Musical Stage

1870s-1880s:

Burlesques and Pantomimes

by John Kenrick

(Copyright 1996; revised in 2020)

(The images below are thumbnails – click on them to see larger versions. This page repeats some information found in Musicals101's History of Burlesque.)

British Imports

Lydia Thompson, the audacious British showgirl who's troupe

of blonde beauties made burlesque musicals a sensation in America.

Lydia Thompson, the audacious British showgirl who's troupe

of blonde beauties made burlesque musicals a sensation in America.

Full length burlesque musicals were almost as lavish as extravaganzas, but aimed their comedy at specific plays, operas, books or legends, with a bit of sex appeal thrown in. The first Broadway burlesques appeared in the 1840s, with story lines that allowed lower class audiences to laugh at the habits of the rich -- or at the high-minded plays and operas the rich admired. Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice was spoofed in Shylock: A Jerusalem Hearty Joke (1853), and Verdi's popular opera Il Trovatore inspired a burlesque called Kill Trovatore! (1867).

These burlesques were disposable theatre works, designed to run for a week or two before being swiftly forgotten. None of the scripts survive, but we know that the scores were entirely borrowed, the comedy low and heavy handed. Burlesque moved to a new level of popularity when English star Lydia Thompson and her troupe of "British Blondes" came to Broadway in a mythological spoof entitled Ixion (1868 - 104).

Click here to see an original cast program for Ixion.

This is an actual size image, so it may take a few moments to download.

Featuring women in both male and female roles, and all clad in revealing tights, Thompson's production set off an uproar. That may not sound like much today, but in the 1860s, proper women hid every angle of their body beneath bustles, hoops and frills. So the spectacle of young ladies in tights acting as sexual aggressors was a powerful challenge to the status quo.

In addition, Thompson and her troupe combined good looks with impertinent humor in productions written and managed by a woman -- no wonder men and adventurous wives turned out in droves. From early on, burlesque performers believed that published material was too easy to steal, so there were no scripts. Thompson and her imitators incorporated popular songs of the day into the action.

Demand for tickets was such that Ixion moved to Niblo's Garden, the same huge theatre where The Black Crook had triumphed two years earlier. All told, Thompson's first New York season grossed a then-extraordinary $370,000 (the equivalent of over $6 million today). Her impact on the future development of popular entertainment in America was tremendous.

"Without question, however, burlesque's principal legacy as a cultural form was its establishment of patterns of gender representation that forever changed the role of the woman on the American stage and later influenced her role on the screen. . . In 1869, the display of the revealed female body was morally and socially transgressive. The very sight of a female body not covered by the accepted costume of bourgeois respectability forcefully if playfully called attention to the entire question of the 'place' of woman in American society."

- Robert G. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1991), pp. 258-259.

At first, the press praised Thompson's burlesques, but soon turned vicious under pressure from prominent do-gooders. Editorials and sermons condemned burlesque as "indecent," which only made the form more popular. Copycat burlesque companies soon appeared, some with female managers. These companies quickly fell under male control, and burlesque evolved into a form of variety entertainment. (More can be found on this in Musicals101's History of Burlesque.)

Burlesque Extravaganzas

Henry E. Dixey

as Adonis (1884), a marble statue that comes to life and does not

find human existence all it is cracked up to be.

Henry E. Dixey

as Adonis (1884), a marble statue that comes to life and does not

find human existence all it is cracked up to be.

Broadway soon developed a homegrown form of burlesque, sometimes described by scholars as burlesque extravaganzas. Produced with lavish stage effects, these musicals spoofed any number of targets simultaneously, ranging from literary classics to contemporary celebrities.

Edward E. Rice dominated this burlesque musical genre, becoming America's first prominent stage composer and producer. As a producer, he brought eighteen burlesque musicals to Broadway, and sent dozens of companies out to tour the United States. Instead of relying on borrowed songs, his shows had original scores. With no formal musical training but a solid sense of melody, Rice dictated tunes to an assistant. His scores graced two of Broadway's most popular burlesques –

- Evangeline (1874) took its title (and little else) from Longfellow's popular poem. It became a surprise success during a summer run at Niblo's Garden. Rice then mounted a more lavish Boston production and brought it into New York for a much longer run. There were plenty of young ladies in tights, and a bizarre, confusing plot that whisked audiences from Africa to Arizona. The material was clean, and family audiences enjoyed seeing a spouting whale, a dancing cow, and comedian James S. Maffit's wordless performance as the inscrutable Lone Fisherman. This jumble toured the U.S. for more than a decade, periodically returning to New York. The 1885 revival ran 251 performances, and marked the Broadway debuts of future stars Fay Templeton and Lillian Russell.

- Adonis (1884 - 603) was Rice's most popular hit. A variation on the Pygmalion legend, it told the story of a gorgeous male statue that comes to life and finds human ways so unpleasant that he chooses to turn back into stone. In the title role, co-author Henry E. Dixey became a matinee idol. Respectable Victorian women flocked to admire his muscular legs, which were displayed in alabaster colored tights. An able comedian, Dixey frequently added new gags and celebrity impersonations. Fans returned time and again, helping Adonis to become the longest running Broadway musical up to that time. The program described the title character follows:

"Adonis: An accomplished young gentleman, of undeniably good family, inasmuch as he can trace his ancestry back through the Genozoic, Mesozoic and Palaeozoic period, until he finds it resting on the Archean Time. His family name, by the way, is 'Marble.'"

Click here to see an original cast program for Adonis

This is an actual size image, so it may take a few moments to download.

In an 1893 interview, Edward Rice offered his definition of the burlesque musical and explained the importance of casting the right kind of performers:

"Is there a difference between burlesque and extravaganza? Decidedly, yes; a subtle one, yet (it) sharply defines. An extravaganza permits any extravagances or whimsicalities, without definite purpose. A burlesque should burlesque something. It should be pregnant with meaning. It should be pure, wholesome, free from suggestiveness. It should fancifully and humorously distort fact. It should have consistency of plot, idealization of treatment in effects of scenery and costumes, fantastic drollery of movement and witchery of musical embellishment. It should be performed by comedians who understand the value of light and shade, and the sharp accenting of every salient point. Strong personality and individual peculiarities are invaluable to the burlesque artist. Passive, negative temperaments go for nothing. Their possessors move on and off the stage unnoticed. It is the man or woman with nervous force, individuality, magnetism who compels the attention of the audience, and this is equally true in tragedy, comedy or burlesque."

- as quoted in The Morning Journal, June 1893

Burlesque musicals continued to thrive through the 1890s. Rice's final production was Excelsior Jr. (1895), another Longfellow spoof that enjoyed a profitable run thanks to a stellar performance by Fay Templeton.

Pantomimes: Clowning Around

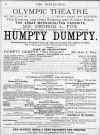

Program

for an 1873 revival of Humpty Dumpty starring George L. Fox, who

eventually performed the title role more than 1,400 times.

Program

for an 1873 revival of Humpty Dumpty starring George L. Fox, who

eventually performed the title role more than 1,400 times.

One act musical pantomimes had been a London and Broadway staple since the 1700s, sharing the bill with other entertainments. By the mid-1800s, American pantomimes placed figures from Mother Goose stories in varied settings, then gave a mischievous fairy an excuse to transform them into the characters taken from commedia dell’ arte (Harlequin, Columbine, Clown, etc.). Using the silent language of gesture, these clowns then had to contend with a variety of comic situations and misunderstandings. The humor was mostly physical, relying on a succession of slapstick routines. This material was accessible to audiences of all ages, including those with little or no proficiency in English.

A typical pantomime script consisted of detailed stage directions with a few snippets of inserted dialogue. The otherwise mute clowns could burst into song to lighten the mood, or whenever the audience and battered cast needed a breather. With colorful sets and athletic antics, this glorified form of children's theater proved to be popular with adults, many of whom were immigrants who did not mind the absence of English dialogue.

The most successful American pantomime musical was Humpty Dumpty (1868 - 483), with comic actor George Fox in the title role. The plot (if you can call it that) transformed Humpty and his playmates into harlequinade characters romping through such diverse settings as a candy store, an enchanted garden and Manhattan's costly new City Hall. With a lavish ballet staged by David Costa (choreographer of The Black Crook), there was plenty of spectacle to offset the knockabout humor.

The score was sometimes credited to "A. Reiff Jr.," but it was largely assembled from existing material, a mish-mosh of recycled Offenbach and old music hall tunes. No one paid much attention to the songs. Fox's buffoonery was the main attraction. Humpty Dumpty set a new long-run record, was revived several times and inspired a series of sequels.

Click here to see a sample scene from Humpty Dumpty

Fox's mute passivity set him apart from the clamor surrounding him on Humpty Dumpty's stage, and audiences took the little man to their hearts. Counting revivals and tours, he played Humpty more than 1,400 times. Advanced syphilis (an all too common--and then incurable--affliction among traveling performers) warped Fox's mind, and after pelting an audience with props during a performance in November 1875, he was forced into retirement, dying two years later at age 52.

Pantomime survived in England as a lighthearted form of Christmas entertainment, but faded from American stages by 1880. American audiences were looking for something more intimate than burlesque and less childish than pantomime. The time was right for an innovation – the form we now know as "musical comedy."